- Home

- Sanam Maher

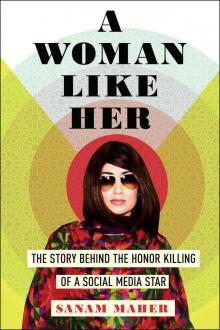

A Woman Like Her Page 5

A Woman Like Her Read online

Page 5

The event has been put together for a TV channel to celebrate one of its dramas airing a hundred episodes. A representative from the channel tells Khushi that he’s brought over the awards that will be handed out to the show’s actors, producers and directors. She goes over the guest list with him. He insists that two army brigadiers be seated on a crystal-studded cream-coloured leather sofa placed at the runway’s halfway point. Other guests include gym instructors and a property developer.

The event includes a fashion show, live music and a children’s tableau before the prizes are given out. “May Allah reward your hard work,” the man murmurs to Khushi as he looks around the hall, which is usually rented out for weddings. An electrician has finally hooked up the lights, and Khushi watches as the catwalk glows in flashes of red, blue and green. “Inshallah,” she says fervently.

Her real name is not Khushi—“happiness” in Urdu. Like Qandeel, none of the girls here use the names their parents gave them. Just a few days after she was born, Khushi’s father was promoted. He worked for the national flag carrier, Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), and he named his baby girl after a dear friend, an air hostess. When this friend heard about the promotion, she came over with a box of mithai (sweetmeats) and gave the infant her first taste of sweetness, letting her lick a dab of honey from her finger. “Look,” she said to the new father. “Her arrival has brought happiness into your home.”

On the morning of 8 October 2005 Khushi was sitting outside her family home in Dhirkot, Kashmir, a little over three hours away from Islamabad, with her cousin. The two girls chattered away as they dipped pots into the cool stream of water that ran by the house. At 8:50 a.m. the velvet green blanket of shisham trees on the hills around Khushi’s home seemed to shimmer like the surface of the stream. The ground trembled. Khushi remembers screaming her sister’s name, not knowing if she answered because she could not hear a thing over the ringing in her ears. “Thirty-two hours later we finally found her in her bed, covered in concrete,” Khushi says. “When the earthquake came, she probably didn’t understand what was happening.”

Seventy-five thousand people died that day. It was one of the worst natural disasters Pakistan had experienced. It was the month of Ramzaan, and after the rains stopped, after Eid went uncelebrated, the aid workers finally arrived. Fourteen-year-old Khushi and her four sisters spoke English, Urdu and Kashmiri, and were snapped up to help interpret for the international rescue teams streaming into the valley. By the time Khushi was fifteen, she was earning 25,000 rupees a month working with a community-based development project. “My father no longer had his job with PIA and our home was a pile of rubble,” Khushi says. “We desperately needed the money, but my father insisted that I continue to go to school. I’d just started ninth grade, and I would go to work after classes.”

Three years later, even as billions of rupees changed hands for development programmes and reconstruction efforts, children were still studying under the open sky and going home to clusters of temporary settlements. One day Khushi travelled to a village near Dhirkot, where the residents pleaded with her to help them get a school rebuilt. Their children had to walk to another village to go to school and many had dropped out because they couldn’t make the journey. Khushi knew there wasn’t much she could do. It was her job to interview locals, listen to their problems, create an agenda and present it to her employers. Aid trickled down slowly.

“I went home and told my father that I needed 30,000 rupees to help out a friend who was getting married,” Khushi says. “Then I walked straight back to the village with that money and my savings.” The villagers learned that she was terrified of water, and every day while the school was under construction three or four people would escort her across the swaying bridge over the river that ran beside the village. Eleven years after the quake, the village still does not have a proper mosque, and Khushi hopes to return some day with enough money to get one built. “I want to help build the mosque with my own hands,” she says. “That’s my wish. Inshallah.”

Khushi left Dhirkot for the ruins of Muzaffarabad, just twelve miles from the quake’s epicentre, to work for a Turkish NGO rebuilding schools and hospitals, but after six months the work had wrapped up and she was without a job. A friend mentioned an opportunity at a furniture shop in Islamabad that sold expensive, intricately carved wooden pieces to the city’s bubble of foreign aid workers, diplomats and journalists. “I travelled to the capital for an interview and I was told, ‘Your education isn’t good, your way of talking is not good, and we need an educated girl,’ ” she recalls. She then applied to a real-estate firm in Islamabad where she was hired as a receptionist. She moved in with her brother and his wife in January 2009.

“Everything was new for me, and everything was different,” Khushi says. “I only knew the village.” Her boss was kind to her, treating her as a daughter while she struggled to find her feet. “There were [foreigners] there and I was expected to serve them alcohol even during the day when they would come for meetings,” she says. Soon her boss’s son was offering her alcohol. “He would say, ‘Come to parties with me, come sit with me, have a drink with me,’ ” she explains. “‘I told my boss, ‘If I wanted to do bad things, I could go anywhere in Islamabad. I don’t need to work here.’ ”

When she left that job, she spent three months doing nothing. Her engagement to a man she had met in Islamabad had ended, and she had no work. By then she had become the primary breadwinner in her family. “My brothers are good boys, but when their wives are around, their colours change,” she says bitterly. “They don’t make that much, and whatever money they bring home, they hand over to my sisters-in-law. That’s just the way it is.” Back in Dhirkot, her parents had come to rely on the 15,000 rupees she had sent home every month. In Islamabad she paid half the rent, another 15,000, to stay in her brother’s apartment. She needed to make some money and fast.

When her sister sent her the designs for some clothes she wanted made, Khushi got her tailor to make copies. The clothes sold, and she set up a small boutique named after her mother, Gulshan. “I even had one or two designers stock their clothes with me,” Khushi says. “We would split the money fifty–fifty.” Soon she was selling shoes, costume jewellery and purses. Two years later, however, the boutique was gutted in a blaze. Her stock of clothes was burned to ashes.

“I was very disheartened,” Khushi says. She was back to being unemployed. “I just went back to my village and I cried for two weeks.” She lay in her bed, unable to move. What now? she remembers thinking. How could she start again from scratch? But when she looked around her home, still without doors as her parents struggled to put things back together slowly after the quake, she knew there was no other way. She had to go back to Islamabad.

When she returned to the city, she applied for every position she could find. At her first job interview a man at a marketing firm sneered at her. “I was wearing a shalwar kameez and had a dupatta on my head,” she says. “I didn’t wear make-up. This man said to me, ‘Sorry, you don’t meet our standards.’ Yes. That’s exactly what he said, can you believe it?” The next few interviews weren’t too different. “Why are you wearing a hijab?” “Your clothes aren’t so nice.” “Don’t you have branded clothes?” She rattles off the responses she got. “Sometimes I would laugh about it. But it made me cry. What country was I living in where I couldn’t get a job because I wore a hijab?”

She finally found work with a retailer who paid her 8,000 rupees a month to visit markets and convince shopkeepers to stock his shampoos, soaps and perfumes. She had earned 40,000 a month with the real estate company and struggled to make ends meet. The daily excursions to the market frightened her. Some shopkeepers were polite and sent her away with chai paani (refreshments). Others leered at her, asking her more and more questions about the products so she would linger, stroking her fingers as she handed them a bottle of shampoo or body wash. She lasted six months.

<

br /> Khushi’s father had always wanted her to be an air hostess. “You’ve got the height,” he would remind her. “Your sisters do not.” One evening a friend pointed out the same thing. “You’re a tall girl,” he mused. “Ever thought about modelling? You could make a lot of money very fast.” His girlfriend Aliya was a budding designer and she needed someone for a shoot, he told Khushi.

But when Aliya met her, her face fell.

“I could see that she didn’t like the look of me,” Khushi remembers.

“We’ll need to do a lot of changing with you,” Aliya sighed. Khushi had never been to a beauty parlour in her life. “We’ll need cutting, we’ll need a dye,” Aliya complained.

“I just thought, Who would make all that effort for me?” Khushi recalls. “Who would spend that kind of money on me?”

But Aliya rejected her anyway, saying, “Your thighs are too big.”

Khushi reached out to her former boss at the real-estate company for help. She had known him since she was eighteen, and despite his son’s behaviour, she’d stayed in touch. “Lose some weight and I’ll pay for a makeover,” he promised her. He introduced her to a photographer, who offered to put her in touch with some models who could mentor her. She needed a portfolio, a Facebook account, and a diet, the photographer advised. Khushi spent the next few weeks looking up exercise videos on YouTube and lost ten kilos by the end of 2015. Once she’d had a few photographs taken, her brother created a Facebook page for her and uploaded the images. Soon there was a message blinking in her inbox: “I’m having a show tomorrow. Can you come audition?”

“Do not wear a shalwar kameez when you go to the show,” advised Summi, a model who had befriended her. “Shalwar kameez don’t work here, and the only ones that do are the branded ones. Get yourself some jeans.”

Khushi had never worn a pair of jeans in her life. She called her photographer friend in a panic. “Don’t worry,” he reassured her. “My friend will take care of you.” He dispatched her to a shop in one of the largest malls in Islamabad, where a girl helped her choose four pairs of jeans and some shirts. When the time came to pay, the bill was a whopping 35,000 rupees. “They were branded clothes, you see,” she explains. “Mango.” Her former boss was called in to help. “I tried to pay him 10,000 rupees for the clothes, but he refused to take it from me,” Khushi says. “I kept thinking, I’ve never taken money from anyone in my life before. I felt so ashamed, but I took it quietly. I didn’t have a choice.”

Back home, she timidly stepped out of her room to show her brother and sister-in-law her new outfits. “You’ve taken to wearing jeans and shirts, now don’t start wearing anything less,” her brother said, joking. She draped a big shawl around herself and headed to the rehearsal.

“Walk,” commanded the show’s organizer. Khushi took a few steps forward and the other models sniggered. “If you want to wrap your big shawl around you and walk the runway, then sit at home with a chadar draped around you,” she snapped. “Take off your shawl.” Khushi pulled it off, but kept tugging at her shirt as she crept forward. Once she reached the end of the runway, she froze. “I didn’t want to turn around and walk back,” she recalls, laughing. “I didn’t want anyone to look at my bum in those jeans.”

The organizer needed to see her walk in heels. Khushi had never owned a pair. “I was five feet nine!” she exclaims. “Why would I wear heels?” She was sent to the nearest market to purchase a pair of four-inch heels and then went home and put them on, tottering around so she could learn how to walk without stumbling.

The next day she went to the Pearl Continental Hotel in Islamabad for the show. The organizer pulled her to one side. “Walk with confidence,” she advised. “Don’t look around you. Just look right at the camera. Just think—there’s only the lights, the camera and the applause. Look haughty, just like the professional models.”

Her walk wasn’t great, but Khushi got through the show without falling over. As far as she was concerned, that was a win. Once the photographs from the show came in, she put them up on Facebook. A few days later a male model messaged her. “Stop working for these smalltime coordinators in these shows,” he told her. “If you want to make it in this industry, you need to meet Mec.”

* * *

—

Mec is one of those men who you cannot imagine ever having been a little boy. It’s as if he’s never been without his distinctive handlebar moustache, his brightly patterned satin ties, jackets that are a touch too long and shoes with an extra wedge of heel. He doesn’t try to convince you otherwise. How long has he been in this industry? “It’s been so long, I can’t even remember.” But if he had to estimate? “You could say that 80 percent of the models here in Islamabad were brought into this industry by me.” How did all these girls find him? “Is that even a question? Everyone here knows Mec.” How long has he been working with Khushi? “From the very beginning. Ever since I’ve been in this line of work.” “It’s been a little more than a year,” Khushi, who is sitting with us, interjects.

It’s the day of Khushi’s show, and when the girls arrive they throw their arms around Mec’s neck and bend to hug him where he is perched on a black pleather sofa. His face rises like a flower and they air-kiss him twice, their lips hovering near each rounded cheek with a smacking Muah! Muah! Yesterday, a new girl came to Khushi’s rehearsal. She had come to Islamabad from Peshawar and wanted to work with Mec. Her head was covered with a dupatta and she wore a shalwar kameez with long sleeves that trailed past her wrists. She was quiet, lingering outside the circle of girls flitting around Mec. She’s back today, her head uncovered. Someone has had a chat with her about how Mec likes to be greeted. She sidles up to give him a kiss and a quick hug.

The girls arrive in packs of three or four, clamouring for Mec’s attention from the moment they enter the room.

“Sir, look at my dress!”

“Sir, where is my dress? I need to see if I brought the right make-up.”

“Sir, I’ve brought my own dress. It’s a bridal dress, sir—it’s so beautiful.”

They are bright and lovely, with tumbles of caramel or blonde hair, eager as kittens. Each one wants to be the girl Mec likes today, the one with the best make-up and most beautiful outfit, the one who will be the last to walk the runway. The showstopper. Mec is known to play favourites. “Sometimes, if a model catches his eye, he will forget the others in the rush to promote her,” Khushi says. “Selfies on Facebook, special shoots, nice clothes, videos for YouTube.”

Mec turns to the girl who has brought her own outfit. “Put it on and show me,” he instructs.

“Sir!” She pouts. “What do you mean, sir? Sir, [my dress] is outstanding, trust me.”

She gets a laugh out of him. “Behave yourself,” he chides.

She giggles. The others seem to wilt.

They pull handfuls of sparkly silk and satin from their bags and he leaves the room so they can change. He pauses at the door. “Girls! Girls, listen,” he says. He claps his hands. “Girls, you need to take care of your things, OK? Put everything in your bags and take it all backstage. Everything goes there. Nothing stays in this room.” They nod in unison like schoolgirls on a field trip.

Mec is nervous about this show. It’s for a TV channel, so that means he couldn’t promise promotion to any other media outlets. “Now if I can’t do that, then why would any designers give us their clothes?” he complains. The channel has a small budget for this event. It’s not the kind of show he is used to. There are only twelve girls walking the runway and they’ll get their make-up done at a parlour. “They didn’t even have a budget for a make-up artist! Just imagine!” There’s only one designer who has agreed to participate, and he is currently on his way over from Peshawar with the clothes on the back seat of his car. “No showsha, no glamouring, you know?” Mec sighs. He pulls out his phone to find out when the designer will arrive.

“Where have you reached?”

The man cannot hear him. He repeats himself. There’s no answer.

“Where are you?” Mec snaps.

The voice crackles on the other end.

“Lo. You told me you’d be here at eleven a.m.”

There are some excuses about traffic.

“Just come. Quickly.” He sulks. “I was going to remind you to get me some paneer. Now forget it.”

The man says something that gets a wide smile from Mec. “OK, baba, OK. Thank you. Come. We’re all waiting for you.” Mec hangs up. He looks mollified. “You know, the cheese in Peshawar is excellent. And this designer is coming from there, as I told you. Bring me some, I told him. He’s bought me a kilo. A kilo!” One of the girls walks in. She wears a heavily embroidered kameez that cinches under her breasts and flows out.

“Sir, isn’t it beautiful? Didn’t I tell you?” she asks. She sways from side to side. The sequins on the fabric are motes of light.

Mec agrees that it is beautiful.

“Can I wear my tights under this?”

He gives his permission.

The girl turns to leave and then pauses. “Sir, can you get the toilets cleaned? It’s smelling so much.”

Mec gives her a tight smile. “Sweetie, can’t you see that I’m giving an interview here?” he says in a sing-song voice. “Is this the time to talk to me about toilets?” Any chance she had of being the showstopper vanishes. “They love me a lot, you know,” he says, watching the girl walk away. “Poor things rely on me.” He taps one cheek and then the other. “One will kiss me here, and another here. They’re like this with me. We are like a family.” And these days one particular member of the family has Mec wrapped around her finger.

He introduces her with a flourish. “Meet Qandeel Two! QB2! Miss Bushi!” he says when she arrives at the venue. She walks almost on tiptoe in her platform heels, gingerly taking one tiny step at a time as though she is afraid to fall over. Bushi is a small, doll-faced, twenty-two-year-old girl from Abbottabad. Her hair falls in tangles to her waist, and she has thick bangs that she caresses to the side every time she talks. She features in every video Mec posts on Facebook these days. There’s Bushi lip-syncing a Bollywood song in the back seat of a car; Bushi at Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s tomb in Karachi, pointing out his grave; Bushi wearing sunglasses as big as saucers, playing with her hair and stroking her necklace as she whispers, “I am Barbie doll;” Bushi in full bridal make-up at a salon, asking, “I’m looking hot, na?”

A Woman Like Her

A Woman Like Her